Cabinets of curiosities (known in German loanwords as Kunstkabinett, Kunstkammer, or Wunderkammer; Cabinets of Wonder, and wonder-rooms) were collections of unusual objects. The term cabinet originally described a room rather than a piece of furniture. Modern terminology would categorize things as belonging to natural history (sometimes faked), geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, art (including cabinet paintings), and antiquities. The classic cabinet of curiosities emerged in the sixteenth century, although more rudimentary collections had existed earlier. In addition to the most famous and best-documented cabinets of rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe formed collections precursors to museums.

Cabinets of curiosities served as collections to reflect their curators’ particular interests and as social devices to establish and uphold societal rank. There are said to be two main types of cabinets. As R. J. W. Evans notes, there could be “the princely cabinet, serving a largely representational function, and dominated by aesthetic concerns and a marked predilection for the exotic,” or the less glorious, “the more modest collection of the humanist scholar or virtuoso, which served more practical and scientific purposes.” Evans explains that “no clear distinction existed between the two categories: all collecting was marked by curiosity, shading into credulity, and by some universal underlying design.” A corner of a cabinet, painted by Frans II Francken in 1636, reveals the range of connoisseurship a Baroque-era virtuoso might evince

In addition to cabinets of curiosity serving as an establisher of socioeconomic status for its curator, these cabinets served as entertainment, as particularly illustrated by the proceedings of the Royal Society, whose early meetings were often a sort of open floor to any Fellow to exhibit the findings his curiosities led him to. It is important to note that the Fellows in this period supported the idea of “learned entertainment,” or the alignment of learning with entertainment. This was not unusual, as the Royal Society had an earlier history of a love of the marvelous. Eighteenth-century natural philosophers often exploited this love to secure their audience’s attention during their exhibitions. However, purely educational or investigative, these exhibitions may sound.

Places of exhibitions and areas of new societies that promoted natural knowledge also seemed to create the perfect idea of civility. Collections of curiosities (as they were typically odd and foreign marvels) attracted a broad, more general audience, which “[rendered] them more suitable subjects of polite discourse at the Society.” some scholars propose that this was “a reaction against the dogmatism and enthusiasm of the English Civil War and Interregnum” This move to politeness put bars on how one should behave and interact socially, which enabled the distinguishing of the polite from the supposed familiar or more vulgar members of society. A subject was considered less suitable for polite discourse if the curiosity displayed was accompanied by too much other material evidence. It allowed for less conjecture and exploration of ideas regarding the shown interest. Thus, many displays included a concise description of the phenomena and avoided any explanation. Quentin Skinner describes the early Royal Society as “something much more like a gentleman’s club,” an idea supported by John Evelyn, who depicts the Royal Society as “an Assembly of many honorable Gentlemen, who meete inoffensively together under his Majesty’s Royal Cognizance; and to entertaine themselves ingenously, whilst their other domestique avocations or publique business deprives them of being always in the company of learned men and that they cannot dwell forever in the Universities.”

History

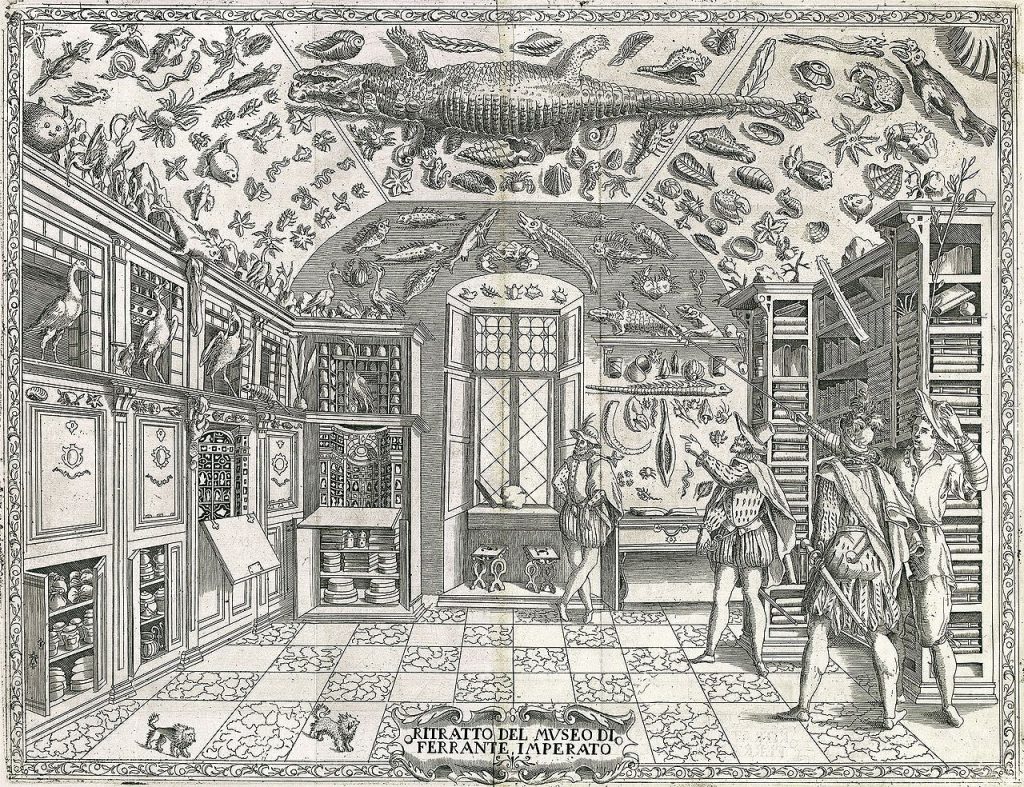

The earliest pictorial record of a natural history cabinet is the engraving in Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’Historia Naturale (Naples 1599) (illustration, left). It authenticates its author’s credibility as a source of natural history information, showing his open bookcases at the right. Many volumes are stored lying down and stacked, in the medieval fashion, or with their spines upward, to protect the pages from dust. Some of the books doubtless represent his herbarium. Every surface of the vaulted ceiling is occupied with preserved fishes, stuffed mammals, and curious shells, with a stuffed crocodile suspended in the center. Examples of corals stand on the bookcases. At the left, the room is like a studio with a range of built-in cabinets whose fronts can be unlocked and let down to reveal intricately done nests of pigeonholes forming architectural units filled with small mineral specimens. Above them, stuffed birds stand against panels inlaid with square polished stone samples, doubtless marbles, and jaspers or fitted with pigeonhole compartments for models. Below them, a range of cupboards contains specimen boxes and covered jars.

In 1587, Gabriel Kaltemarckt advised Christian I of Saxony that three types of items were indispensable in forming a “Kunstkammer” or art collection: firstly, sculptures and paintings; secondly, “curious items from home or abroad”; and thirdly, “antlers horns, claws, feathers and other things belonging to strange and curious animals.” When Albrecht Dürer visited the Netherlands in 1521, apart from artworks, he sent back to Nuremberg various animal horns, coral, some large fish fins, and a wooden weapon from the East Indies. The highly characteristic range of interests represented in Frans II Francken’s painting of 1636 (illustration, above) shows images on the wall that range from landscapes, including a moonlit scene—a genre in itself—to a portrait and a religious picture (the Adoration of the Magi) intermixed with preserved tropical marine fish and a string of carved beads, most likely amber, which is both precious and a natural curiosity. The sculpture is both classical and secular (the sacrificing Libera, a Roman fertility goddess) on the one hand, and modern and religious (Christ at the Column) are represented, while on the table are ranged, among the exotic shells (including some tropical ones and a shark’s tooth): portrait miniatures, gem-stones mounted with pearls in a curious quatrefoil box, a set of sepia chiaroscuro woodcuts or drawings, and a miniature still-life painting leaning against a flower-piece, coins, and medals—presumably Greek and Roman—and Roman terracotta oil-lamps, a Chinese-style brass lock, curious flasks, and a blue-and-white Ming porcelain bowl.

The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (ruled 1576–1612), housed in the Hradschin at Prague, was unrivaled north of the Alps; it provided solace and retreat for contemplation that also served to demonstrate his imperial magnificence and power in a symbolic arrangement of their display, ceremoniously presented to visiting, diplomats and magnates. Rudolf’s uncle, Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria, also had a collection, organized by his treasurer, Leopold Heyperger, which emphasized paintings of people with exciting deformities, which remains largely intact as the Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Austria. “The Kunstkammer was regarded as a microcosm or theatre of the world and a memory theatre. The Kunstkammer symbolized the patron’s control of the world through its indoor, microscopic reproduction.” Peter Thomas states of Charles I of England’s collection succinctly, “The Kunstkabinett itself was a form of propaganda.”

Two of the most famously described seventeenth-century cabinets were those of Ole Worm, known as Olaus Wormius (1588–1654) (illustration, above right), and Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680). These seventeenth-century cabinets were filled with preserved animals, horns, tusks, skeletons, minerals, and other interesting human-made objects: sculptures wondrously old, wondrously fine, or wondrously small; clockwork automata; ethnographic specimens from exotic locations. Often, they would contain a mix of fact and fiction, including apparently mythical creatures. Worm’s collection included, for example, what he thought was a Scythian Lamb, a woolly fern supposed to be a plant/sheep fabulous creature. However, he was also responsible for identifying the narwhal’s tusk as coming from a whale rather than a unicorn, as most owners of these believed. The specimens displayed were often collected during exploring expeditions and trading voyages.

In the second half of the 18th century, Belsazar Hacquet (c. 1735–1815) operated in Ljubljana, then the capital of Carniola, a natural history cabinet (German: Naturalienkabinet) that was appreciated throughout Europe and was visited by the highest nobility, including the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II, the Russian grand duke Paul and Pope Pius VI, as well as by famous naturalists, such as Francesco Griselini and Franz Benedikt Hermann. It included several minerals, including mercury specimens from the Idrija mine, a herbarium vivum with over 4,000 Carniolan and alien plant specimens, fewer animal specimens, a natural history, a medical library, and an anatomical theatre.

Cabinets of curiosities would often serve scientific advancement when images of their contents were published. The catalog of Worm’s collection, published as the Museum Wormianum (1655), used the collection of artifacts as a starting point for Worm’s speculations on philosophy, science, natural history, and more.

Cabinets of curiosity were limited to those who could afford to create and maintain them. Many monarchs, in particular, developed extensive collections. A relatively under-used example, stronger in art than other areas, was the Studiolo of Francesco I, the first Medici Grand-Duke of Tuscany. Frederick III of Denmark, who added Worm’s collection to his own after Worm’s death, was another such monarch. A third example is the Kunstkamera, founded by Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg in 1714. Many items were bought in Amsterdam by Albertus Seba and Frederik Ruysch. The fabulous Habsburg Imperial collection included important Aztec artifacts, including Montezuma’s feather head-dress or crown in the Museum of Ethnology, Vienna.

Similar collections on a smaller scale were the complex Kunstschränke produced in the early seventeenth century by the Augsburg merchant, diplomat, and collector Philipp Hainhofer. These were cabinets in the sense of furniture made from all imaginable exotic and expensive materials and filled with contents and ornamental details intended to reflect the entire cosmos on a miniature scale. The best-preserved example is the one given by Augsburg’s city to King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden in 1632, which is kept in the Museum Gustavianum in Uppsala. As a modern piece of furniture, the curio cabinet is a version of the grander historical examples.

The juxtaposition of such disparate objects, according to Horst Bredekamp’s analysis (Bredekamp 1995), encouraged comparisons, finding analogies and parallels and favored the cultural change from a world viewed as static to a dynamic view of endlessly transforming natural history and a historical perspective that led in the seventeenth century to the germs of a scientific theory of reality.

A late example of the juxtaposition of natural materials with richly worked artifice is provided by the “Green Vaults” formed by Augustus the Strong in Dresden to display his chamber of wonders. The “Enlightenment Gallery” in the British Museum, installed in the former “Kings Library” room in 2003 to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the museum, aims to recreate the abundance and diversity that still characterized museums in the mid-eighteenth century, mixing shells, rock samples, and botanical specimens with a great variety of artworks and other human-made objects from all over the world.

In seventeenth-century parlance, both French and English, a cabinet came to signify a collection of works of art, which might also include an assembly of objects of virtù or curiosities, such as a virtuoso would find intellectually stimulating. In 1714, Michael Bernhard Valentini published an early museological work, Museum Museorum, an account of the cabinets known to him with their contents’ catalogs.

Some strands of the early universal collections, the bizarre or freakish biological specimens, whether genuine or fake and the more exotic historical objects, could find a home in commercial freak shows and sideshows.

Important Collections that started as Curiosity Cabinets

- Ashmolean Museum Oxford — Ashmole and Tradescant collections

- Boerhaave Museum in Leiden, the Netherlands

- British Museum in London — Sir Hans Sloane’s and other collections

- Chamber of Art and Curiosities, Ambras Castle in Austria remains intact

- Deyrolle in Paris

- Fondation Calvet, Avignon

- Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden

- Kunstkamera in Saint Petersburg, Russia

- Pitt Rivers Museum (Oxford, England) — Ex-Ashmolean Dodo

- Teylers Museum in Haarlem

- Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan

- World Museum in Liverpool – XIIIth Earl of Derby collection

In Modern Times

The idea of a cabinet of curiosities has also appeared in recent publications and performances. The Houston Museum of Natural Science houses a hands-on Cabinet of Curiosities, complete with a taxidermied crocodile embedded in the ceiling a la Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’Historia Naturale. In Los Angeles, the modern-day Museum of Jurassic Technology anachronistically seeks to recreate the sense of wonder that the old cabinets of curiosity once aroused. In Spring Green, Wisconsin, the house and museum of Alex Jordan, known as House on the Rock, can also be interpreted as a modern-day curiosity cabinet, especially in the collection and display of automatons. In Bristol, Rhode Island, Musée Patamécanique is presented as a hybrid between an automaton theatre and a cabinet of curiosities and contains works representing the field of Patamechanics, artistic practice, and area of study chiefly inspired by Pataphysics.

For example, Cabinet magazine is a quarterly magazine that juxtaposes unrelated cultural artifacts and phenomena to show their interconnectedness in ways that encourage curiosity about the world. The Italian cultural association Wunderkamern uses the theme of historical cabinets of curiosities to explore how “amazement” is manifested within today’s artistic discourse. In May of 2008, the University of Leeds Fine Art BA program hosted a show called “Wunder Kammer,” the culmination of research and practice from students, which allowed viewers to encounter work from across all disciplines, ranging from intimate installation to thought-provoking video and highly skilled drawing, punctuated by live performances.

Several internet bloggers describe their sites as a wunderkammer either because they are primarily made up of links to interesting things or because they similarly inspire wonder to the original wunderkammer. The researcher Robert Gehl describes such internet video sites as YouTube as modern-day wunderkammer. However, they are in danger of being refined into capitalist institutions, “just as professionalized curators refined Wunderkammers into the modern museum in the 18th century.”